History of cement PROMPT Natural Cement

Cement's history, inseparable from concrete's one, is in the 20th century a story of the rediscovery of materials, constantly evolving craftsmanship, and an architectural transition between craftsmanship and industry.

Discover our storyHistory

Natural cement's origines…

"Natural cements, first cements discovered in the early 19th century, were widely produced in Europe until the First World War. They were initially used as additives for lime, then as binders for creating castings in the stucco-style, and finally for manufacturing artificial stones.

They gave cement its prestige and they allowed concrete to prove its architectural capabilities.

1830-1910's period represents a transition from classical construction in dressed stone to the modern technical and aesthetic design of reinforced concrete. Regions such as the French Alps, particularly Isère and Grenoble, played a significant role in this transition due to the quantity and quality of constructions made with PROMPT natural cement. These constructions continue to exist and are now being valued, and cement factories still produce these cements for their occasional restoration purposes as well as for the development of new products and architecture."

Cédric Avenier, History/Architecture/Architectural Workshop Doctor

Early 19th century

Used by Egyptians and Romans, cement became a technological product after its rediscovery by Louis Vicat

Invention

Technologic revolution

Fast-setting natural cement was a true innovation in its time.

CONSTRUCTIONS

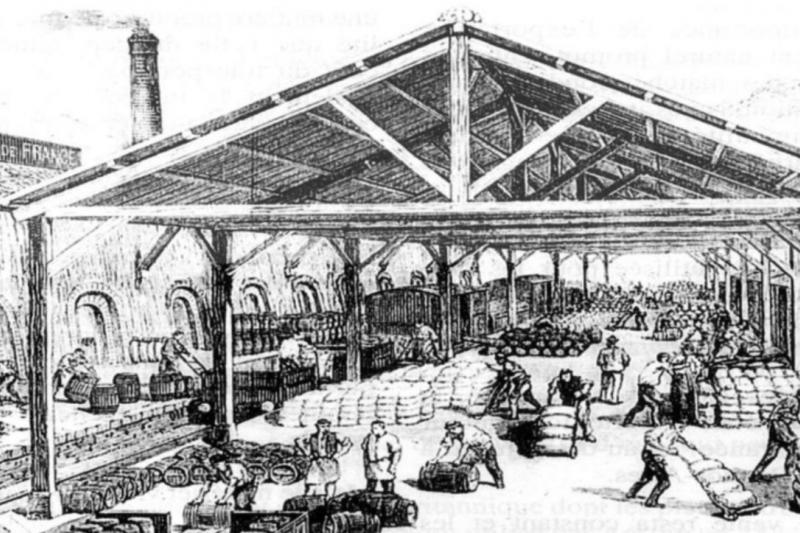

Natural cements, also known as Roman cements, played a significant role in numerous 20th-century constructions, including bridges, roads, canals, and port facilities. Engineers greatly appreciated their four main properties. First and foremost, their rapid setting and hardening allow the structures to be secured against bad weather or cold temperatures. Other qualities included the mortar's strengths, the structures' durability, and the distinctive aesthetics provided by the fast-setting cement's unique ochre color.

An Innovative Material

Since the famous Roman mortars made of a mixture of sand, lime, and pozzolana (a rock consisting of volcanic ash), no progress had been made in the field of hydraulic binders until the end of the 17th century.

The first advancements were noted in England. In 1796, James Parker, an English lime burner, discovered a limestone with sufficient clay content that, after being fired at 900°C, produced a fast-setting natural cement. He subsequently patented the process of firing nodules of Septaria rock. This groundbreaking invention demonstrated that a hydraulic binder could be created by low-temperature firing of a limestone with a higher clay content than the lime typically used. This could be achieved without slaking the burnt stone but simply by grinding it, which was not the case with lean lime or lime-pozzolana mixes used at the time.

In the early 19th century, this process spread throughout continental Europe, using the firing of marl, a clayey limestone. This cement was then mistakenly referred to as "Roman cement." However, this term was not appropriate because, contrary to its name, it did not involve rediscovering the mortars used in Roman times.

Denomination

Natural cement or Roman cement

Natural quick-setting cement, or incorrectly referred to as "Roman cement" in its early days, is the first cement in the modern sense of the term.

In the 19th century, there was confusion regarding the terms used to refer to cement. Natural cement, quick-setting cement, Roman cement, plaster-cement... The most accurate denomination today is that of "natural quick-setting cement".

End of 19th century

A growing success

Fast natural cement provides an economical and sustainable solution for the decoration of facades. It perfectly imitates stone without the high cost, giving a yellowish ochre color with hints of brown instead of gray, which gives it a remarkable patina over time.

Fast natural cement is used for:

- Template-based molding, replacing the more expensive traditional stucco and creating a decorative mortar coating on walls of buildings typically made of bricks.

- Mold casting, whether prefabricated or not, which has gained widespread popularity as a replacement for plaster.

- Concrete applications to imitate stone. It offers a 100% natural, economical, durable, and aesthetic solution that recreates the appearance of stone.

- It is used as a hydraulic binder with rapid setting properties, providing effective solutions for construction works, especially those in aquatic environments, due to its waterproofing and water resistance properties.

- It played a significant role in the development of the precast industry, particularly in the production of water conveyance pipes. Pipes made from natural cement have better resistance to aggressive water than those made from Portland cement or artificial cement of that time.

- It is favored for its ease of manufacturing.

Manufacturing

A simplified manufacturing

The firing of natural cement, carried out at low temperatures (between 500°C and 1200°C) below the melting point, allows the use of marl or clayey limestone with clay proportions ranging from approximately 22% to 35%. As a result, the raw material is more readily available as it is possible to utilize various deposits found almost everywhere.

Artificial cement or natural cement

In 1817, Louis Vicat demonstrated that it was possible to manufacture artificial cement by mixing clay and limestone. However, at that time, the grinding tools and the cost of energy made it difficult to achieve this mixture at a low cost. That is why the "natural" combination of these two components in marls was preferred.

Firing

The firing technology, simple and already existed, was similar to the one used for traditional lime kilns. Unlike lime, Roman cement is simply ground and does not undergo slaking. This firing process has remained the same since the 19th century.

Discover

Discover our product

From a unique deposit located in the Chartreuse massif, PROMPT natural cement is an exclusive product of the Vicat Group.

Discover our realizations

As a reference in restoration & decoration, PROMPT naturel cement is an on markets of eco-construction, quick masonry and water & sanitation.